Hello friends, in case you are looking for what happened to the author of this blog, all of my extant old & new writing on film is archived via the Esotika Film Website, so please check that website.

Wednesday, May 24, 2023

Saturday, March 28, 2015

An Esotika Canon for 2015

The way I think about movies has changed so significantly in the past few years, and this is perhaps why I continue to find it hard to write about film, despite wanting to. I find myself more interested in the exploratory process of watching and responding to films than necessarily finding specific works that highlight or respond to my interests. As such, many of the films listed below sit as either microcosms of larger ideas or as a variable/signifier to indicate a director's entire oeuvre.

I think the largest problem I've always had when considering the construction of a personal canon, something that I've never quite been able to articulate, is that my fascination with horror movies is tied more to the mechanics of the genre than to specific titles. Because of this, I always feel like the lists I make of my "favorite" or "defining" films or whatever are always too light on horror. I'll be the first to say that it's very rare for a horror film to be perfect in any coherent sense, but I think this necessary imperfection is an important element of the genre.

Horror is a genre dedicated to experience, in the sense that the experience of the viewer is privileged over certain elements of Film with a capital F--the experience of watching a horror film is often far more important than the film in and of itself. Similarly, experimental films--at least those that I'm attracted to--privilege viewer experience and thus suffer (if "suffer" is actually the right word) a similar consequence.

With that being said, here is a list for 2015, that I feel comfortable establishing as an "Esotika Canon," which could perhaps be considered a new "Post-Genre Canon," or a Canon for the exploration of UFOs (Unidentified Filmic Objects).

Visitor to a Museum (Konstantin Lopushansky)

Daughters of Darkness (Harry Kumel)

Kairo (Kiyoshi Kurosawa)

I think the largest problem I've always had when considering the construction of a personal canon, something that I've never quite been able to articulate, is that my fascination with horror movies is tied more to the mechanics of the genre than to specific titles. Because of this, I always feel like the lists I make of my "favorite" or "defining" films or whatever are always too light on horror. I'll be the first to say that it's very rare for a horror film to be perfect in any coherent sense, but I think this necessary imperfection is an important element of the genre.

Horror is a genre dedicated to experience, in the sense that the experience of the viewer is privileged over certain elements of Film with a capital F--the experience of watching a horror film is often far more important than the film in and of itself. Similarly, experimental films--at least those that I'm attracted to--privilege viewer experience and thus suffer (if "suffer" is actually the right word) a similar consequence.

With that being said, here is a list for 2015, that I feel comfortable establishing as an "Esotika Canon," which could perhaps be considered a new "Post-Genre Canon," or a Canon for the exploration of UFOs (Unidentified Filmic Objects).

Visitor to a Museum (Konstantin Lopushansky)

This is the first film I'd seen in ages that literally floored me, found me exhausted, totally drove me into an interior space of explosive permutation. This film is terrifying and sad, indicative of a cosmic finitude that finds us alone. There is a thought that this should be experienced again, soon, and perhaps spoken of in longer form, but as the initial experience was so corporeal, I worry about the lessening.La vie nouvelle (Philippe Grandrieux)

While the narrative of Sombre directly appeals to my taste in stories more, La Vie Nouvelle takes precedence because of what it does with the medium of film. Grandrieux is a very important filmmaker for me because he understands & has pushed forward the idea of film as a direct experience for the viewer (rather than an empathetic experience). The catalog of techniques of affect present in La vie nouvelle is astounding.

Daughters of Darkness (Harry Kumel)

Delphine Seyrig, perfect soundtrack, endless & empty hotel. Functioning, in my mind, as an unintended sequel to Last Year at Marienbad, this is a narrative genre film that still manages to contain a scene of such singular intensity it's rarely matched: Seyrig speaks of the Countess Elizabeth Bathory to the young couple, she holds her blue drink, reflective light takes on the shape of a diamond in the soft focus of the camera's filter, Seyrig's voice is so controlled, so modulated, it's as if the camera is circling her in a dizzying whirlwind, the story continues, and it's a story of terror, the young wife cannot take it, Seyrig is still speaking but there's an air of silence--and then the young wife actually cannot take it any more, she erupts. The tension is developed to such a point that one could, as the expression goes "cut it with a knife"--but in this case, the thickened air actually is cut, and that wound serves as the crux of the entire film.Pentimento (Frans Zwartjes)

A film I have watched only once, long ago at this point despite a repeated intention to re-visit, but a film that haunts my headspace, a confluence of memory and dream: what I really love about this movie might not even be there. But, as such, this film becomes a perfect vessel to deliver that specific idea. Film as a medium should be able to exist in interstitial space between memory and invention. What I can remember: an abandoned institute, doctors and nurses, women, high heels, running in the mud, violence, entrails spilling out, impossible colors, the perfect drone of Zwartjes' synth soundtrack, a feast, class relations, allegory or narrative, distance, the cold, iciness. Can connect in the head to several other lesser (though still worthwhile) films, overwhelmed by narrative instead of imagery: Lifespan, with its circling Terry Riley soundtrack; Footprints, with its moon-man trauma; & perhaps even to the recent Errors of the Human Body, which displaces trauma into the late-capitalist experience of greed. But what is it that unites these films? Pentimento stands far apart, but the construction of a network serves to heighten all four.La femme du gange (Marguerite Duras)

The universe that Duras constructed in the 70s and early 80s--through a network of novels, plays, films & short texts--is an endlessly fascinating narrative universe. The Vice Consul as a novel, India Film as a play, L'Amour as a text and La femme du gange as a film, feel, to me, like the most important elements of this universe (despite, perhaps, the fact that The Ravishing of Lol V Stein is literally the launching point). While it is perhaps India Film or The Truck that get the most attention out of Duras's oeuvre, I think there's a calm and quiet brilliance--an intensity in the sense of light--that haunts this film. We move back and forth between the beach of S. Thala & the interior of a hotel--is this the ballroom where it happened? There's whispering, questions... Also, I believe this was the first time that Duras articulated what would become her trademark technique in film, allowing the voice-over text to not always match up diegetically with the events on screen, though there is always a tension present that helps create meaning. There's something to be said of, perhaps, the necessity to experience Duras's films without subtitles, as she developed an idea of narrative based around the idea of hearing someone read in opposition to reading--something, of course, impossible without being to speak French. This is where the problem comes from with India Song, and why La femme du gange takes precedence above it.Dead Mountaineer's Hotel (Grigori Kromanov)

Elements: a mystery, perhaps a murder; isolation, brought about by snow storm; secrets, perhaps cosmic secrets; and above all, a hotel--a beautiful and impossible hotel of black walls decorated by neon, ballrooms filled with Krautrock tinged synth-prog--together this is a narrative space that I want to spend time within. This film is pure joy on an aesthetic level, and perfect melodrama in how the plot develops--and the movement from mystery to sci-fi works perfectly instead of at a level of denigration to the plot.Martyrs (Pascal Laugier)

My interest in this movie seems to repeatedly surprise people--or at least it's seen as a 'questionable' opinion, but since it's pretty much positioned itself into my brain and stayed there for like.... 7 years? I'm willing to recognize that it belongs on a list like this. There's so much I like about this. On a formal level, I love that it literally uses the archetypes of genre to pull a 'bait and switch' coming at the almost-exact half-way point--which I also would maintain continues to function beyond the level of "first viewing experience twist" (if considered as movements as in a musical score, the latter is of course informed by the former but redirects expectations and, more importantly, on the level of affect it provides a disorientation). Again, on a formal level, I also love how the second act borrows from historical incidents of JOY IN THE FACE OF DEATH, even tweaking reality (which seems to be something I've seen people complain about, despite the fact that movies are not real) to fit the current of the film (this is also perhaps a very Bataillean movie when considered with any sort of gravitas). It is imperfect (for example, the montage scenes in the second act accompanied by very over-the-top "emotional" music threatens to disrupt how well the film works), but it is important and brilliant.Beyond the Black Rainbow (Panos Cosmatos)

I love everything about this movie. I saw it three times in theater during the two weeks it was playing San Francisco. I have watched it multiple times since then. In terms of aesthetics this is 100% Perfect. Colors, Film Quality, Architecture, Music, Dialogue. The narrative exists exclusively in the realm of atmosphere, which is the mode in which I most appreciate plot. The heshers at the end arguably break the diegesis, but there's also a pleasure in how entirely unnecessary the scene is. While I recognize this movie exists exclusively in consideration of cult genre films that came before it, Cosmatos learns from the films he's clearly obsessed with instead of just stealing scenes & ideas from them (in the way someone like Tarantino does)--as such, the movie is entirely his own. It has a lineage, but it is entirely contemporary to the present.L'important c'est d'aimer (Andrzej Zulawski)

I refer to this, when I'm asked, as "my favorite movie of all time." The way I view film makes putting a singular film into that position difficult, but after a few years and countless re-watches, it seems that the sentiment remains. I was asked, once, why it was this film, more than any of Zulawski's others, that I loved the most. It's a complicated answer, but there are two key points, I believe, that offer some sort of explanation. First, perhaps moreso than any other film like it, everything in the diegesis of the film occurs at a limit. As such, it's perhaps one of the most important limit-texts in all of film. There is an extremity, a desperation present. The mise-en-abyme of the film also speaks worlds about the nature of art and performance, while this is weaved into an impossible relationship that drives the core of the film: the impossible love that Fabio Testi's character feels for Romy Schneider's character. Movement in a Zulawski film always feels choreographed like dance, but here the choreography is an emotional choreography. Secondly, Fabio Testi's character/Fabio Testi himself is just so unbelievably attractive to me on such a deep level, both physical an in terms of actual Character. I would like to note, however, that save for a few details (some not explained here), much of Zulawski's work could sit in this position: Possession, La femme publique, Szamanka or perhaps even L'amour braque.

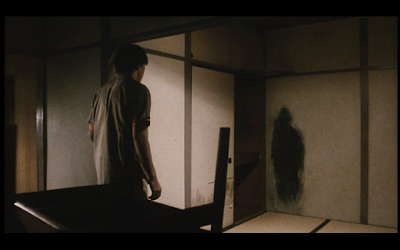

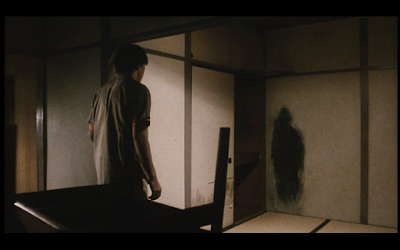

Kairo (Kiyoshi Kurosawa)

It's always a bit of a toss up between this film and Kurosawa's Cure--on any given day I could perhaps give a different answer. However, there's something that feels so overarching about this film, it feels like it extends into everything. Much of Kurosawa's work has this feeling, but in Kairo it's incredibly fine-tuned. This came out in 2001, but the ideas of the film (if not the technology) feel so utterly contemporary--for what has been discussed more in philosophical circles lately than the state of the anthropocene & the development of AI? I regularly find myself drawn to films which carry a simultaneous "iciness" and heavy emotional core at the same time. Kairo is a masterpiece because it manages to flatten out any hierarchy of importance between the characters--they're all interchangeable, virtual players in the geocosmic trauma of the world: humans are unimportant when considered in the larger picture, and I can't think of another film that manages to say this so well without being explicitly didactic.Invisible Adversaries (VALIE EXPORT)

EXPORT's film is revolutionary in its refusal to settle into anything definable. It's markedly queer while maintaining a heterosexual female as its protagonist, it's narrative driven despite the fact that there is no Grand Narrative dominating the film, it explodes into moments of EXPORT's performance art. I find it shocking that so few people tire of male-dominated cinema at times, and EXPORT's film is a perfect antidote to this exhaustion.Querelle (Rainer Werner Fassbinder)

This is, on a deeply personal level, the perfect cinematic manifestation of desire. It manipulates lust and desire with more intensity than any pornographic film. It creates a longing, an ennui, with narrative. The artifice is necessary and perfect, for how else could a citadel of eroticism be constructed within film? Fassbinder's final film, similar to EXPORT's film, is a stringent revolt against both lazy eroticism and the inherent binaries that drive a commonplace understanding of desire. Which is to say: this is an explicitly queer movie that traffics in masculinity without positing it as a supremacy. Even the captain, played so perfectly by that other stud of Italian genre cinema--Franco Nero, in his longing, displays a variant eroticism: self-driven eroticism that is not repressed, but rather dependent upon the object being unattainable.Naked Blood (Hisayasu Sato)

Sato is a director I have a bona fide obsession with. As such, there are many many films of his that warrant mention, so one might question why I chose his (arguably) most well-known film for the list. Before I re-watched this last year (as half of a brilliant double feature, paired with The Kirlian Witness) I remembered it as little more than a gore-fest. But the strange--for want of a better word--"art house" elements that pepper much of Sato's pinku films are on full display here, to devastating effect. A woman deep frying and eating all the parts of her own body, a woman who becomes orgasmically responsive to piercing her flesh with jewels, these set-pieces actually recede into the ether in comparison with the story that drives the film here. A father disappears into a burst of light on a family trip, and the son he leaves behind spends his life trying to attain a scientific success out of debt to the absence. Life is incomplete until a woman who communicates telepathically with a cactus is introduced. It all ends in death, as everything does, but the route we're taken on to arrive there is beautiful and strange.Anatomy of Hell (Catherine Breillat)

Breillat wanted to adapt Duras's The Malady of Death (which is one of my favorite books) but could not get the rights, so instead she wrote her own book based on The Malady of Death (Pornocracy) and then turned it into a film. It's a beautiful film--I feel like this is a movie that reveals more about women than anything else. Accusations that the movie is "homophobic" are so entirely off point and only reinforce a patriarchal structure of understanding: the man in this film (played by the beautiful & well endowed Italian porn star Rocco Siffredi) is not important. This is a film about women, for women. Breillat refuses to let men into the film. And for that reason, this film is not only necessary, but also brilliant.Blue Movie (Alberto Cavallone)

There's a reality to Cavallone seeming infinitely more interesting in theory than in practice, but when his films work, they work exceptionally well. Blue Movie tackles trauma from so many various angles, while simultaneously masquerading (and at times, performing as) an exploitation film. The film is a nightmare of closed spaced, amped up because the only exterior scenes are scenes of violation: as such, there is no space to feel safe. There can be no difference between inside or outside. As a structural metaphor of the inescapability of trauma, this is brilliant. And the film collides such desperation and intensity with a smartly considered (and apparently completely missed by most viewers) critique--another example of a cinematic limit-text.Outside Satan (Bruno Dumont)

I was very late to the game with Dumont, but as I've now seen all of his films except for Humanité, he has firmly established himself in my head as a completely necessary director. While he's often compared to Bresson for his philosophical & political underpinnings and use of non-actors, I find Dumont much more rewarding (which is not to sell Bresson short by any means) in perhaps his contemporary subjects--this is a man who is making films about what it means to be alive right now. Outside Satan was my introduction to his work, and as such holds a place of importance. Also, since in many ways Dumont has made the same film multiples times, Hors satan is perhaps my favorite permutation of that narrative (it should go without saying that not all of his films are the same film, but Life of Jesus - Hors satan - P'tit Quinquin seems like variations on a theme).Mil Sexos Tiene la Noche (Jess Franco)

Consider this film as a signifier of Franco's entire Golden Productions period, which for me is without question Franco at his best. I literally love work from all points of his oeuvre, and there are still so many more films of his I've yet to see, but in considering what I'm interested in film doing, the Golden Productions serve that mode best. Mil sexos tiene la noche is perhaps my favorite due to two things: 1) set almost entirely within a hotel, 2) the dominating theme of hypnosis. The entire film is carried by through a somnolent ennui: peaks never quite peak & the entire film flattens into fugue. The first time I saw this was on a non-subtitled transfer that had bizarrely blown out & hyper-saturated colors--these elements helped serve the disorientation the film offers. Franco is someone regularly deserving of attention.Vite (Daniel Pommereulle) / Deux fois (Jackie Raynal)

These two films, for me, stand in for all of the films of the Zanzibar film group. It perhaps could be seen as a sin to praise the Zanzibar group without mention of Philippe Garrel, but while I love La lit de la vierge, Pommereulle's elliptical and hermetic Vite, along with Raynal's astutely smart & challenging renegotiation of materialist film each bring something unique to cinema. I feel a similar joy and attraction with the films of Franco Brocani & Marcel Hanoun--these are all films that are located in some unnameable quadrant where feature-length narrative films collide with pure experimentation & the political/philosophical play of the late 60s and early to mid 70s.The Films of Dore O & Werner Nekes

I know very little about either half of this power-couple, but I know that the films both were making individually, and the films they made together, are unquestionably beautiful and hermetic. Like fever dreams of affect, the fugue of aesthetics. At some point I will spend more time and perhaps figure out something more specific, but this is all I can speak to for now.The Pornographic Films of Phil Prince & Roget Watkins

These films are all dark and nasty, yet they exist in the liminal space of an early 80s New York City that is dripping with... something. I can't articulate precisely what is about Phil Prince's bizarre low-budget sleaze-epics that appeal to me, but there's such abjection and vitriol present on screen that a hyper-space of eroticism is recreated as something no one could slide into without any sort of traumatic introduction. It's the bizarre nature of his films that I find appealing: they're simultaneously cheesy and sleazy, disturbing and hilarious. But, what makes the films work best of all is the presence of George Payne, who inhabits the sadistic characters found in Prince's films so perfectly. There's an energy that I want to compare to that of Klaus Kinski--it's that sort of screen presence [note: I also find Payne almost Paynefully (get it) attractive, a corporeal response is always almost guaranteed]. Watkins pornographic features function differently, as they're far more narrative than Prince's. Corruption and Midnight Heat hold as much pathos and revelation as any of Abel Ferrara or Paul Schrader's films. Corruption specifically offers a sensual derangement that leads to a nightmarish journey through the self as visualized with corridors and secrets behind hidden doors. Probably half the stories in my book Slow Slidings are in some way or another indebted to Watkins.Related films that offer indications to an expansive sense of this personal canon:

- And Then There Were None (Peter Collinson)

- Manhattan Baby (Lucio Fulci)

- The Taking of Deborah Logan (Adam Robitel)

- The various permutations of the films of the Vienna Actionists

- Institute Benjamenta (Quay Brothers)

- Last Year at Marienbad (Alain Resnais)

- Gradiva Esquisse 1 (Raymonde Carasco)

- The specific position of Eurohorror, though perhaps weakened in any sort of guiding notion, is still occupied by Alain Robbe-Grillet, Jose Benazeraf, Jean Rollin, Renato Polselli, Vicente Aranda, Michele Soavi, Lamberto Bava, Álex de la Iglesia & Eloy de la Iglesia

Friday, February 05, 2010

Franco’s Golden Productions

My article on Jess Franco's Golden Films International productions is now live on the Severin blog.

I'll be posting it on the redesigned Esotika website in the future as well.

I'll be posting it on the redesigned Esotika website in the future as well.

Sunday, June 21, 2009

ARREBATO (IVAN ZULUETA, 1979)

I have had this film for 3 or 4 years now, and really, I should have seen it long ago. I was only missing out. However, thanks to the wonderful film communities that have sprung up stronger since I acquired my initial bootleg, English subtitles now exist for the film. As mesmerizing as its images are, what gives this film its power are the ideas that are present. The images are hypnotic, having what the film itself could potentially describe as "occult rhythms," but without an idea behind the sublimity present in the super 8 film that populates the film, we'd be left with nothing but aesthetics.

There are several ways I would characterize my relationship to film: First and foremost, I am obsessive. Secondly, I find that a story works best (or is most interesting) when rooted primarily in abjection and the uncanny. I think abjection is an important term when considering this film. For me, the loci of abjection and the uncanny in cinema is met when genre film--particularly horror--intersects experimental. This is an allowance of the fantastic with an allowance of materiality, a performative necessity (as in the film itself is performing an act as we, the viewers, are watching), and an insistence that the qualities of film (image music text; movement, narrative) can achieve more than the inherent, assumed qualities of what is considered the classical Hollywood narrative achieve.

Arrebato itself is at the threshold of genre and experimental cinema. Finding itself with one foot in both worlds, meshed together perfectly, it is a cinema of ideas, a cinema of power. It is a cinema of abjection. We'll start with this.

It's easy to turn to the theoretical construct--developed primarily by Julia Kristeva--of abjection when discussing the horror genre. A primary element of abjection is the idea of "letting go of something we would still like to keep."1 A dismembered arm, from the perspective of the amputee, is abject. Horror cinema is often a cinema of viscera: "blood, semen, hair and excrement/urine, we recognize these as once being a part of ourselves, thus these forms of the abject are taken out of our system while bits of them remain in our selves."

According to Kristeva, since the abject is situated outside the symbolic order, being forced to face it is an inherently traumatic experience. For example, upon being faced with a corpse, a person would be most likely repulsed because he or she is forced to face an object which is violently cast out of the cultural world, having once been a subject. We encounter other beings daily, and more often than not they are alive. To confront a corpse of one that we recognize as human, something that should be alive but isn't, is to confront the reality that we are capable of existing in the same state, our own mortality. This repulsion from death, excrement and rot constitutes the subject as a living being in the symbolic order.

Arrebato is located in the space of abjection. It's narrative drive is the idea of the "rapture" (the literal translation of "arrebato"), a semi-mystical state of heightened being, a "pause," as Pedro, who is developing the rapture refers to it. When we are first introduced to Pedro, he does nothing but shoot film, an obsession that, we find out, helps him to keep from eating, sleeping, fucking, or shitting for prolonged periods of time. He lives in a state of hysteria, wildly crying as he watches the short fragments of film that he has shot. The only time he can calm down, the only time he can face the reality of humanity, is with the help of "dusty-dust"--heroin.

While Pedro drives the narrative of the film, it is through the world of Jose-- a filmmaker and heroin addict--that this narrative unfolds. Structurally, the narrative of Pedro is embedded within the Narrative of Jose, until the end when the two collapse into each other (almost ontologically). As the film begins Jose is editing a film, a vampire feature that he is visually dissatisfied with. He arrives home from his apartment, after being gone two weeks for a shoot, to find his lover who had formerly left forever, and a parcel from Pedro containing a key, a reel of Super8 film, and an audio cassette.

Eventually Jose sits down to listen to the tape, which retells the story of Jose's interactions with Pedro, as well as the development of Pedro's filmic alchemy. Upon initially meeting Jose, Pedro recognized something special in him, something that isolated Jose as an ally to Pedro's esoteric cause. while Pedro's haunted voice presents the idea that what it is that Pedro can "see" is something mystical, it's obvious to the audience that the only thing that these two men have in common is an utter obsession with the cinema. As Jose remarks early on in the film, “It’s not that I like cinema… it’s cinema that likes me." Jose is presented as akin to real world filmmaker Jess Franco-- despite the fact he doesn't always feel satisfied with what he's done, he has to be making films. Pedro's obsession has already been explained, taking up literally all of his time. For better or worse, both Pedro and Jose are addicted.

This cinematic addiction is paralleled by Jose's relationship with Ana--his ex-lover who formerly left. Their relationship, normal at first, quickly devolved into an intense bond dependent upon heroin to keep it together. The heroin/relationship subplot helps to heighten the intensity of the film, the desperation present, a motivation for the film's denouement: a material example of obsession.

But now we must return to the idea of abjection: "The concept of abject exists in between the concept of an object and the concept of the subject, something alive yet not." Let's consider re-writing this sentence as: What appears on film during cinema exists between the concept of an object and the concept of the subject, something alive yet not. Film's materiality captures a representation of a physical place, a physical person, an action that is literally happen. But what we see when we watch a film is not the actual physical place, it's not the real person, it's not the actual action: what we see is an image. What we see is neither live nor dead; rather, it's a representation of the image.

And this is what the film is about: Arrebato presupposes that film can be more than a representation--it suggests that film has power, and as Roberto Curti points out in his brilliant article on the film, "the image of an object put on film does not share the same ontological reality as that of the filmed object." Eventually, both Pedro and Jose become nothing but film. They are no longer ontologically present in the physical, material world at the end of the film. Rather, they become pure simulacra--a copy without an original. They are ontologically film. The vampiric nature of the camera, brought to life through Pedro's "occult rhythms," has sucked people out of the real world into "film-world."

It is through this ideological construct that a simple jump-cut removing an actor from the frame becomes terrifying. Obsession leads to men away from the "real" world and into something else. A metaphysical afterlife that can be seen but not felt. Pedro knows that he is going to ostensibly "die" as the red pauses on his developed film become longer and longer, yet he prepares himself for and faces his "escape" with both desperate terror and a severe insistence. There is utter beauty in the desperation, and we can feel it in all of Pedro's footage, the pulsing, rhythmic representations of the world moving at an intense tempo: the moon crossing the sky, a penis erecting with the air of flora in bloom, clouds erasing the blue of the air with a mask of white, people moving through life, etc., etc. These images are cinema's pulse, the bloodstream that keeps it alive.

Arrebato itself echos the ideas that it diegetically presents: the film itself holds power over the viewers, calling upon desperation and rhythmic images, coupled with a compelling storyline, to cull the viewer into an active trance-like state. It is mysterious, enigmatic, and compelling. It is a film.

1: All quotions pertaining to abjection come from http://www.artandpopularculture.com/Abjection

Sunday, June 14, 2009

LANDSCAPE SUICIDE (JAMES BENNING, 1986)

Upon initially hearing about this film, I was fascinated by it's combination of structuralist film techniques and a narrative looking into the lives of two very different murderers. I was a bit hesitant to watch the film for a while due to Benning's reputation: from what I understand, he has a tendency to make films full of static shots of landscapes with little to no narrative, films that they tend to be long, considering they seem to be structural experiments (most of Benning's filmography averages the length of a normal cinematic feature, an hour and a half).While organizing some of my movies the other day, I re-encountered my copy of this film and decided to ignore my expectations and watch it.

The film ostensibly examines two murderers: 16 year old Bernadette Protti, who killed a classmate for no discernible reason; and the infamous Ed Gein, who, as any horror fan knows, was the prototype for cinematic manifestations of terror ranging from Norman Bates in Psycho to Leatherface in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. However, it's Benning's techniques, and how he approaches his source material, that make the film something exciting.

The film is fragmented into two segments, the first half "examining" Bernadette Protti, the second Ed Gein. Each half is approached in the same manner, beginning with what I'll call a prolonged "establishing" shot. The shot sets the tone for the landscape that each crime is taking place in. Protti's story begins with six minutes of a woman repeatedly practicing her tennis serve, representative of the useless banality of life in the suburbs. Gein's half begins with an extended static shot of a desolate, Midwestern landscape: an overcast sky, dead plantlife-- an emotional void.

Following each establishing shot, Benning shots more static landscapes of various elements of each subculture that the murders are rooted in: the posh suburbs and the Midwestern heartland. Eventually fragmented information, delivered via voice-over narration, begins to hint at the subject matter that the film encounters. After many of these flat, banal shots, the viewer encounters the "meat" of each segment: an interview with the murderer reconstructed from "actual court transcripts."

It is during these icy scenes that the film acquires a very abject and emotional core. Benning's camera stares directly at the subject as they answer questions posed by an interviewer off-screen. The actors playing the murderers are flat and unemotional: to viewers they are virtually inhuman.

Protti proves to be the more interesting subject, as Gein already has a major media presence. If we, as an audience, can assume that the dialogue that Benning's film presents is drawn from an actual transcription, then the flat, impersonal delivery that the actress playing Protti provides perfectly highlights the confusion of adolescence. Protti stares into the camera unable to articulate any sort of motivation as to why she killed her cheerleader-acquaintance, unable to externalize, with language, anything that she is truly feeling. It's terrifying to watch, as Protti is very confused, and, despite the stoicism of the film, it's clear that she is also fairly terrified (albeit not out of grief, but rather of what exactly is happening in her own life, the fact that she has completely lost control).

Following the interview, in each fragment, Benning provides static and dynamic landscape shots, punctuating the landscape inspired trance-state (which is generally accompanied by what is understood as diegetic sound) by including somewhat ironic, yet still abject and remarkably sad scenes accompanied by pop music (in the first half, a teenage girls talks excitedly on the phone while a song from "Cats" plays, in the second half, a latent 1950s housewife archetype dances by herself to Patsy Cline's "Tennessee Waltz"). I get the impression that the banality of each landscape is suppose to draw some parallel to the murders, but the film reads better when we consider the landscape, as it is shown to us, as tainted by the banality of the murders. Shots that had no emotional impact shown before the interview suddenly resonate, and the prolonged nature of each scene inspired uneasiness instead of boredom. It's almost manipulation in a remarkably non-manipulative manner: the film simply offers an objective circumstance in which the viewer can consider the implication of each crime, and landscape.

Wednesday, November 12, 2008

INSTITUTE BENJAMENTA (STEPHEN & TIMOTHY QUAY, 1995)

ESOTIKA CLASSICK 02

I've lost any conception of what it is exactly that makes a movie perfect for me. I once thought it was a primary aesthetic reaction: a culmination of images and music, with some sort of hyperbolic, mimetic emotionality. A sense of poetry-- but not the poetry of the Romantics, or anything hegemonically beautiful, rather, a poetry of violence, excess, of desperation--all contained within a narrative.

But then I discovered the world of experimental cinema and video art. In video art, aesthetics are eschewed in favor of the immediacy that the medium of video offers. There is nothing beautiful to look at, and sound is often terribly muffled, recorded in camera. But that's not what video art is about, video art is about a concept, it's about an idea. Vito Acconci was not a filmmaker, he was a conceptual artist who occasionally happened to work with a video camera. So do we dismiss this from our understanding of "motion pictures" ? Just because the medium of moving images is used in a different way, this shouldn't exclude an entire genre. It's different, and it forces the viewer to reconsider his conception of what a "movie" is. Experimental cinema does this as well: often an experimental film is more about structure (or once again concept). Narrative is almost consistently overlooked (at least in most well known examples: Michael Snow, Stan Brakhage, etc.). We are now, thanks to Greenbergian modernism, looking at the material qualities of film itself. But some of what was originally contained in perfection shines through. Paul Sharits' repetition and strobing seems awful and obnoxious at first, but further reflection reveals there is a poetry of violence and excess there, and, in a roundabout way, a definite sense of hyperbolic emotionality. The images, though not images you would expect to find in a film, turn out to be beautiful too.

So where does that leave me now? I'm not sure. There is one thing that I am sure of though. Seven years ago I watched the Quay brother's first feature length film, Institute Benjamenta at 5AM before I headed off to a day of my Junior year of high school. I thought it was perfect then. Last night, seeing the film for probably the 10th time, I still think it is.

Has nothing changed? I know that I view film now in an entirely different manner from when I first saw the film. My criteria for what works and what doesn't work is completely different. I don't think I suffer any sort of sentimental attachment to the film either, as I've specifically tried to avoid that throughout multiple viewings: I've never let myself tie the film to a particular part of my life. I know there was something special, exciting about the first time (the first time is always different), but repeated viewings have just shown the film to be better, something new, something better.

When I first saw the film, it was a dream that I wanted to escape in. The film works best when paying careful attention to it's construction of atmosphere. It's oppressive, but in a stunning way. Every single line that Alice Krige mutters as Fraulein Benjamenta is labored, forced out, like she is not sure she should even be speaking, but must. There is a immediacy in her vocal intonation that makes her dialog seem present. Mark Rylance, as Jakob, is completely outside of the film the whole time, which is why Fraulein and Herr Benjamenta gravitate to him, "JAKOB with him one could dare something very Big." He is the clown at the funeral of meaning that the Institute claims to offer.

The set design of the film is what initially made the film so magical to me. The antiquated deer/stag parts decorating every mysterious corridor and doorway, the hyper present texture that everything takes on-- all of this lensed through Nic Knowland's (who got his start shooting John Lennon and Yoko Ono's experimental films) utterly brilliant cinematography, recalling, in a more textured manner, the brilliance of Sascha Vierny.

...

There is an awkward tension throughout the film: Jakob's voice over narration often betrays what is happening on screen. We are told that "the inner chambers contain nothing but a goldfish," while our eyes have already been privy to an entire subterranean level, accessed through awkward doorways located in the center of walls, sometimes created by drawing a concentric circle on a blackboard and walking through it while blindfolded. I don't think that the film suggests that Jakob's imagination is running wild under the domain of repression, rather, I think the world is far more mysterious than Jakob is willing to accept.

A dynamic tension is also constructed via the subversion of narrative. Ostensibly, Institute Benjamenta does have a classical narrative structure: the film begins with Jakob arriving at the institute, the climax occurs with the death of Fraulein Benjamenta, and denoument comes with Jakob and Herr Benjamenta leaving the Institute in the snow. However, these three events are only coincidentally related. The arrival of Jakob does not lead to Fraulein Benjamenta's death (she was already virtually dead), nor does the death lead to the end of the institute (Herr Benjamenta tells Jakob he has closed the institute before). It is arguable that the arrival of Jakob leads to the closure of the institute, but reducing the narrative to an "A, then B" structure is reductive, within the context of the larger film.

As I reach this point, I realize once again that I still don't really know what I'm aiming at here. I suppose, really, that what I'm trying to say, to clarify, is that this is a good film. An amazing one.

Friday, July 25, 2008

LUCIFER RISING (KENNETH ANGER, 1972)

ESOTIKA CLASSICK 01

Lucifer Rising exists as an intersection between two filmic ideas, and it is within this intersection that the film gains it's power: more than any other film, Kenneth Anger's Lucifer Rising is about spectacle and hypnosis.

From a level of spectacle the film is pure ritual, literally and figuratively. Juxtaposing mythological images of ancient Egyptian Gods with contemporary Thelemites, Anger delineates the progressive nature of time in order to present to the spectator the necessary elements of the ritualistic form his film is taking. But what makes the ritual appealing to the audience is divorced from this esotericism--it's the nature of the films' aesthetics. Anger's level of artifice is exemplary; hyper-pervasive primary colors permeate every frame, shockingly electrified negative images pop up for brief moments, highlighting both the phenomenon of nature (lightning, volcanic eruptions, the birth of an alligator/lizard) and the exclamation points of banal events (as we tour through the hallway a man absently shuffling a deck of cards suddenly throws them into the air).

Anger's camera--generally static at a fixed angle in all of his films leading up to this one--finally begins to move in the aforementioned hallway scene, which is one of the most enigmatic tracking scenes that I've encountered through all of cinema. As we move through Anger's many tableau with a steady tempo, echoed by the calm score, there is an abject atmosphere of anxiety that arises: the film is telling us that something is going to happen soon, and we don't know what that is, but it's going to be something important.

Bobby Beausoleil's score is another necessary element of the film: composed from his prison cell, Beausoleil's score provides the soundtrack for Anger's film in the only instance where specific music has been produced for the specific film (excluding Jagger's grating drone "composed" for Invocation of My Demon Brother, the rest of Anger's films, as popularly recognized, are simply coupled with 50s and 60s pop music, often to an ironic extent-- there is no irony present in Beausoleil's score for this film). The soundtrack itself is an excellent piece of work, with or without Anger's images married to it. It is a bit psychedelic and ambient, echoing both the naturalistic evocations brought about by Anger's pensive landscape shots, and the internal psychedelia that plays a pivotal role in the film.

Beausoleil's score also plays a major role in elevating the level of hypnosis present in the film; the pulsing score with it's utter repetition and subtle progressive changes feeds directly into the subconscious, the same way Anger's images work their way through cracks. In The Poetic of Cinema, Raoul Ruiz discusses the idea of hypnotic film in his chapter on Shamanic cinema (a more than apt term for Anger's films, to be sure). He sets forth the idea that when a film has an hypnotic element, the viewer may fall asleep. This is not the result of boredom, in fact this opens up, rather, an expanded film for the viewer: the dream world and the film world begin to mesh into a single unity, allowing the viewer to become an alchemist, colliding the "reality" of the film with the subconscious connections the mind brings forth. Being a Thelemite and follower of Crowley himself, an often ignored part of Anger's cinema is the fact that all of his films are "intended as [...] magickal working[s] on the viewer," with Lucifer Rising intending to open "up a wider field of the sublime effects of nature and ancient history" (which relates to the earlier mentioned delineation of past and "present").1

Anger's magick remains esoteric, unknowable to the viewer. But one thing that can be read without occult historical knowledge is the simple repetitions and geometric shapes that pop up repeatedly throughout the film. The aforementioned hallway tracking scene demands attention, and that attention is shattered, popped, at certain moments. There is a level of control that the image has over the viewer. Same with the stoic profiles of the Gods in ancient Egypt; the camera demands attention, and despite what could ostensibly be classified as camp costuming, these images attain a significant importance. Whereas Jess Franco using languid tracking shots and repetition for the purpose of an extension of sexual ennui, Anger uses the same techniques for the purpose of hypnosis. It is, however, worth noting that both Franco's sexual ennui and Anger's techniques of hypnosis have an aim of ensnarement, a goal of pulling the voyeur/spectator into the diegetic world of the film.

The only problem with the film is that from what people expect of Anger (from a locus of popular culture), Lucifer Rising is more of less at odds with what has generated Anger's reputation: it, to a large extent, lacks the hyper structural editing that initially put Anger on the map, as well as being totally devoid of the pop music that Anger pioneered the music video with. It is also not necessarily indicative of the homosexual avant-garde that Anger often gets lumped in with. The often ridiculed "campy" costumes are merely ritualistic signifiers. They are just conduits to a larger idea that is inherent within a much larger system, and reading the images as nothing beyond camp is discredited Anger as an artist, as a magician. But these are all surface level details-- further exploration into Anger's oeuvre reveals that Lucifer Rising is more accurately a culmination of everything Anger learned in making films. The obsessive fetishism of objects and sensory details is present, as is the already mentioned religious strain that permeates all of Anger's films, and all of this makes it easy to see that this is Anger's best film.

1 Moonchild: The Films of Kenneth Anger, edited by Jack Hunter

As both an exercise to get myself back into film writing/watching, as well as a way to make myself come to terms with the way I think about cinema, I'm going to start a series of reviews of 'ESOTIKA CLASSICKS.' Which, instead of writing about the obscure or esoteric films that usually decorate my blog, I will be revisiting more common films that exemplify the Esotika spirit and are a core part of the Esotika canon.