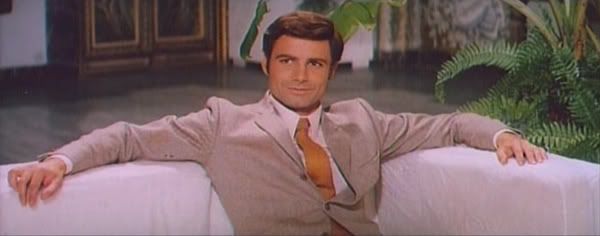

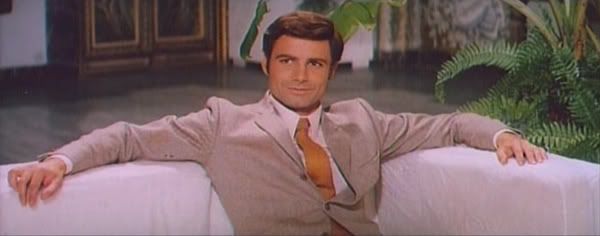

Or, A Primer to Watching European Genre Cinema Sin in soft focus: Udo Kier in Walerian Borowczyk's Blood of Dr. Jekyll

Sin in soft focus: Udo Kier in Walerian Borowczyk's Blood of Dr. JekyllIf you've been reading my blog for a while (hell, or if you've just looked at the sidebar to glance at the titles I've talked about) you're undoubtedly aware of my unwavering devotion to marginal films that most film-snobs would immediately dismiss based solely on their subject matter, and in some cases, undeserved reputation as "bad films." It seems like the films I love, for the most part, got off to an initial, critical start. The horror film (which, when it comes down to it, is really what my beloved films, for the most part, are at heart) has throughout cinematic history been considered a simple "popular" genre, and based on this assumption alone it has been overlooked as a purveyor of cinematic art.

This reputation has provided very interesting opportunities for film makers. Once producers realized that the viewing public would pay money for a movie, and more or less not complain, if it featured enough scares, enough blood, enough actual

horror. So producers allowed themselves to be lazy. They lowered the allowed budgets for these film makers, concerned with nothing but cheap thrills and the desire to make a buck. Because of this apathy towards the movies themselves, horror, as a genre, started to become something special.

It's a blatantly simple thing to understand in both theory and practice. Lack of budgets for special effects or even long enough shooting schedule forced film makers to experiment, to try new things in order to compensate what they considered a short coming. It's amazing how many parallels can be found between experimental cinema and genre cinema throughout history. There's a major difference though; the genre film makers were experimenting in order to achieve the means to a narrative they desired, giving, more often than not, a true

reason for their experiments, as opposed to many films of the avant-garde that were completely not concerned with narrative. Don't get me wrong, I'm an ardent supporter of avant garde and experimental film, but often what it comes down to in response to these films is the fact that they're really interesting and great, but don't accomplish anything.

Genre cinema, on the other hand, takes these innovative stylistic choices, creative use of editing, colors, mise-en-scene, and puts them towards a greater whole; a narrative experience. Aside from 'forced' experimentation, once producers were backing off while simply providing basic requirements that the film makers must meet, genre film directors could do more or less whatever they wanted with the rest of the film. In America a perfect, early example of this would be the films of Val Lewton, a producer at RKO studios who had an extensive hand in all of the films that he 'produced' (and more often then not, wrote, helped direct, helped edited, etc). As a one-man powerhouse, Lewton almost single handedly changed the horror genre from a filmic entity focused on Universal monsters into something decidedly more adult, something with psychological impact and all the same elements that canonical, "important" films of the time had. Even Doris Wishman's zero budget films often had sublime moments that come from her fetishizing ordinary living room objects in such an abject fashion that feeling, a sense of importance, is generated.

A monochromatic scream in Massimo Dallamano's What Have They Done to Solange?

A monochromatic scream in Massimo Dallamano's What Have They Done to Solange?But more to the point, to my heart and mind it is the so called "Euro-Trash" that should hold the crown in cinematic history. It is a genre so diverse and intelligent that I've grown to almost resent its generic title. Euro Trash. The term applied to cinema is generally understood to be referring to blatantly exploitative, generic, incompetent films with loads of naked flesh, gore, and incomprehensible plots. And this is where the resentment comes from, as that description couldn't be farther from what really lies at the heart of what I prefer to refer to as "European Genre Cinema."

As in any subgrouping of film, there are bound to be films that are better than others. There are even bound to be films that really

are utterly unredeemable trash, films that deserve to be delegated to the bottom of the bin and never dredged up from the past. This is just to clarify that I'm not attempting to make a case for an entire genre as a whole. That in itself is more or less impossible to do for any genre, even well regarded and respected ones. There are dire drama films. There are dire noir films. There are utterly dire "art house films" (which, for the record, is another term that I find almost completely empty in regards to

what that actually means). But, also like any subgrouping, there are utterly amazing films. But I'll take it one step further. I would argue that not only are there

some utterly amazing films in the "Euro Trash" subgroup, but rather there are

many. In fact there are so many that the entire genre as a whole deserves to be place up so high on a pedestal that film studies students everywhere suddenly forget about formerly canonized films such as

The Third Man,

The Godfather,

Seven Samurai or even

Citizen Kane. The rewards of "Euro Trash" cinema are unending, accomplishing things that the aforementioned films couldn't dream of accomplishing.

To start it off, in order to not just be sprouting off random examples of why European Genre Cinema is so great, it is necessary to divide ideas into groups of unified aesthetics that the important and rewarding films have to offer. Also, as a preface, I will be making little mention of the films of directors Dario Argento or Mario Bava. They are directors that have been deservedly canonized (more or less), so need no help from me in finding their audience.

THE IDEA OF REPRESENTATIONThe first importance of European Genre Cinema is the implicit understanding the directors had that cinema is not reality. In the same way Magritte made his now infamous "Ceci n'est pas un pipe" painting, which feature a visual representation of a tobacco pipe, European Genre Cinema directors perfectly understand that cinema is not reality. Cinema is an art form that allows the non-real to visual exist in the mind of the viewer. Within this context, what you could term a 'non-realist' viewpoint, there is no necessity for the events in a film to follow the same logic that the everyday world does. A common complain by many viewers is that the film they've just watched "doesn't make sense." This is more or less an empty statement. You could clarify by stating, "This film doesn't make sense according to the laws of reality," but what does that indicate about the film itself? Nothing; for the film itself is

not reality, it is a film. In a films inherent dream logic, why is it an example of a "bad" film if a character dies and then shows up again later in the film, such as in Jean Rollin's darkly lyrical debut feature

The Rape of the Vampire? The film is distanced from reality, vampires don't exist in the real world, so how can we, as viewers, make the assumption that this apocryphal creature, and even the apocrphal non-creatures (existing more or less as representations of what we understand to be humans) have to abide to laws of reality? It doesn't disrupt the flow of the film, rather it extends a parallel filmic universe that we are watching events unfold in.

Also, with film existing as an art form and not reality, European Genre directors often use what is now understood as structuralist film techniques to expand ideas by non-sequiturs. A barrage of scenes that appear to be seemingly unrelated or confusing often with serve to develop an idea that is necessary to the films narrative, such as in the case with Robbe-Grillet's

La Belle Captive where three film worlds are depicted virtually right after each other in order to clarify an

idea. It is not randomness when one scene jumps to another without an obvious connection, an active viewer of the film should have no problem picking up connections

by theme or even juxtaposition.

The endless beach in Jean Rollins Rose of Iron

The endless beach in Jean Rollins Rose of IronAnother major complaint over European Genre cinema, divorced from non-sequential scenes, is the "bad special effects." Once again, to return to the point; why is it a flaw when blood looks fake if the blood

is fake. When a character in a movie dies, the actor portraying the character does not die. Rather, a representation of an idea dies, and the method of death is of little consequence. If a viewer is actively seeking out a representation of death that accurately complies with real life death, he or she is better off watching the news. "Bad special effects" give directors an opportunity to add poetry, or even deeper meaning to a scene. Blood can be representative of more than just blood, it can carry many more connotations.

THE NECESSITY OF NON-ACTING/OVERACTINGAnother oft-heralded complaint of European Genre Cinema is "bad acting." The idea of bad acting relates to the aforementioned category; how can you judge the way a character is acting in a non-real world when you yourself do not exist in that world? If the film is successful then non-acting or even overacting seem complacent, fitting. For example, in many Jess Franco films the actors and actresses are accused of simply "wandering through the film" as some sort of "zombie." Atmosphere is an important element of many of Franco's films, and what is termed "realist" acting would fail to fit within his narrative. Take, for example, Soledad Miranda in the 1970 film

Eugenie de Sade. Miranda does exist in the film as a wide-eyed witness to events that she rarely responsively emotes too, but that's because Miranda's character Eugenie is only a signifier, representing this idea of a naive young girl in response to the terrible events she is taking place in.

The intense emotions of Sam Niell and Isabelle Adjani in Zulawski's Possession

The intense emotions of Sam Niell and Isabelle Adjani in Zulawski's PossessionAndzrej Zulawski is another director who characteristically gets panned for having his actors and actresses constantly screaming and wailing in a completely, once again, non-"realist" manner. This is because Zulawski's characters more often than not are simply signifiers for the emotion that the characters are depicting themselves. The emotions are regularly very extreme, even desperate emotions and a "realistic" portrayal of these emotions would be removing the essence of the emotions themselves. were Sam Niell and Isabelle Adjani to interact with each other without the emotional intensity, nothing would be translating to the viewer, the film would simply be a slightly surreal marriage drama. It is the emotional intensity that heightens the

awareness and

response that the viewer has to the film, and it's brilliantly accomplished.

EROTICISM AND OVERT SEXUALITYAnother key element in European Genre Cinema is the abundance of films that directly or indirectly deal with sexuality. Often dismissed as "soft-core tripe" or "something to be seen on skinemax" there is something very reaffirming about the fact that there were and are directors that care enough about sexuality and erotica to deal with it through artistic, political, and philosophical venues. European Genre Cinema is also one of the few areas of cinema where sex as metaphor is often more successful than sex as sex, and the fact that European Genre Cinema often is connected to the

fantastique further extends the fascinating depictions.

Conceptual S/M in Jess Franco's Macumba Sexual

Conceptual S/M in Jess Franco's Macumba SexualEuropean Genre Cinema is also one of the few areas of world cinema where the essence of Sado-Masochism is explored in a manner fitting to what lies at the heart of S/M. Generally vapidly exploited in mainstream cinema, and dealt with in almost the same way in most European mainstream art-house cinema, European Genre Cinema often, whether through visual, editing, musical, or atmospheric means, hits the nail on the head as far as imbibing the emotional and artistic qualities behind the subculture, often managing to make the S/M far more conceptual, even working to forward the plot.

Despite the fact it’s

technically not an example of European Genre Cinema, Radley Metzger’s

The Image (aka The Punishment of Anne), which was adapted by the novella of the same name by Catherine Robbe-Grillet (under the pen name of Jean de Berg) manages to perfect carry the essential conceptual tone of the novel into cinematic form (to note, while Metzger is an American, many of his films, including

The Image carry the European Genre cinema spirit, and are also generally shot in European locations with European actors and actresses). For an example of a far more conceptual use of S/M, one can look at many of Jess Franco’s films, which often feature S/M scenes as allegory of power dynamics and internal torment.

STYLISTIC VISUALSOne of the most remarkable elements of European Genre Cinema is the fact that a unique visual aesthetic is achieved in almost all of the remarkable films from the subgroup. Even despite the small budgets many films were plagued with, cinematography and set design is almost always a concern. For example, consider the entire sub-genre of gialli films. They were churned out notoriously quick, yet almost ever single film is strikingly decadent in terms of interior design and costume design. These films were meant to be set upon the rich and famous, and without the costume design and interior decorations, this effect could never have been achieved.

Aside from the physical objects depicted in the film, the films also resonate a deeply unique visual tone. Many films adapt very long tracking shots which add a sense of paranoia to the atmosphere (for example, Zulawski’s

Possession), many use static shots to conceal and reveal elements of the frame, and Franco’s notoriously “overused” zoom is actually very effective in certain situations, add an emphasis and shifting focus in ways that would otherwise go unnoticed.

Another very important thing in European Genre Cinema is the use of colors. Most of these film makers knew exactly what they were doing when it comes to color, and examples go far beyond the masterful use of color present in Argento and Bava’s oeuvres. Harry Kumel, for example, in one of the most criminally underrated films of all time (and personal favorite)

Daughters of Darkness, many of the scenes fade to red, a color that is overly pervasive in the film, creating an utter tension in addition to the other meanings that the color takes on.

Nino Castelnuovo in Radley Metzger's Camille 2000FINAL NOTES

Nino Castelnuovo in Radley Metzger's Camille 2000FINAL NOTESOne more small, significantly less intellectual item to note about European Genre Film is fairly obvious: the men and women that are in these films are the most stunningly gorgeous people on the planet, from any time period! The elegantly gorgeous Delphine Seyrig stars in the aforementioned

Daughters of Darkness, stunningly handsome men like Nino Castelnuovo and Fabio Testi decorate many Italian gialli and other genre films, the unforgettable Laura Gemser takes her turn as the Black Emanuelle in many of Joe D’Amato’s best films, and the list goes on and on. If you have any appreciate for aesthetic beauty in human beings of all sorts, then there will always be something to appreciate in a European Genre film!

In conclusion, European “Trash” Cinema is a film genre that deserves just as much recognition as the more canonized genres of film history do. It’s fiercely intelligent and unique, and lives up to and surpasses cinematic standards in all areas. In writing this I’ve realized that almost every idea that’s been brought up could be fleshed out to essay length itself, so I suppose it would work best to consider this as a sort of introduction to the wonderful work of European Genre Cinema.

This article was written for the Trashy Movie Celebration Blog-a-thon.